When I read recently that June Lockhart had died, well into her nineties, an unexpected wince ran through me. The sharpness of that reaction surprised me for just a second but then I thought of Lassie—not just the television show, but my Lassie. And suddenly I was ten years old again, sprawled on the living-room carpet, rolling around with my first pet, an exuberant and impossibly soft collie who shared the name of the heroine on TV.

She and I and my brother and sister watched the show together every week: me wide-eyed, her attentive in that way dogs can be, as if she too were following the adventures of her brave and impossibly intelligent on-screen counterpart.

Those were simple, golden moments. I loved her completely.

But childhood stories often contain a turn, and this one does too.

My mother—whose severe OCD had roots I would not fully understand for another sixty years—found ticks in Lassie’s bedding. What followed was a crisis for Lassie of catastrophic proportions. For me, it was the beginning of something far worse. The fumigators came. The bedding was hauled away. And Lassie herself was banished to a barren side yard behind our house in El Cajon, California.

It was a hellscape of decomposed granite and blistering heat. No shade. No comfort. Her thick collie coat became matted. She smelled. Her paws chafed. Mine did too when I went out to see her.

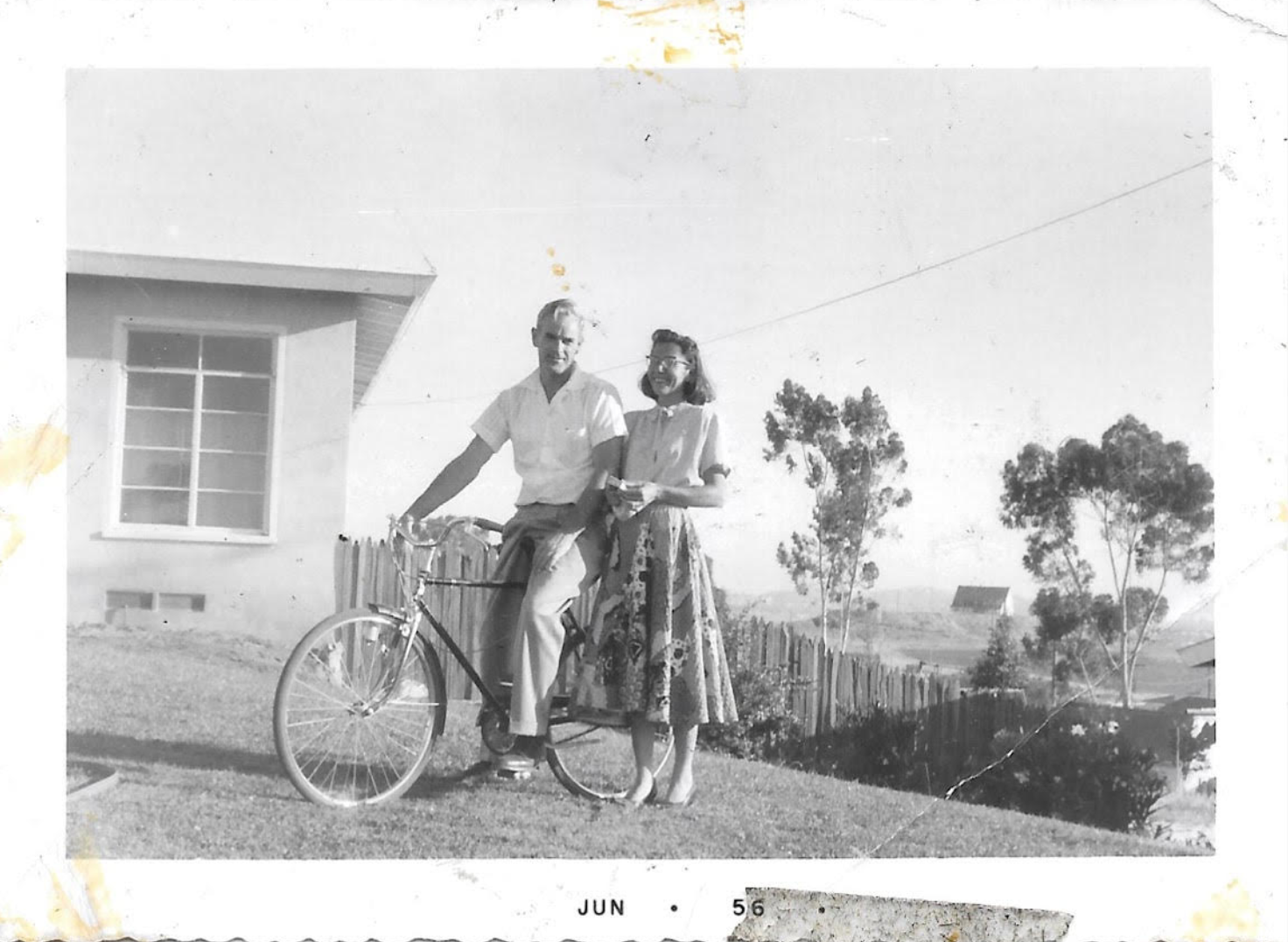

If you were to look at the picture that sits at the top of this article—a black-and-white photograph from 1956 of my mother and father—you would see an ordinary scene from mid-century America. I was eight years old when it was taken. And behind the wooden fence in this photo was the side yard of hell for my dog, where she would be condemned to live just two years after this photo was taken.

My siblings and I were placed on “feed the dog and give her water” duty. But for a ten-year-old, that side yard felt like a dungeon of despair. There was nothing to do there. No rolling on the floor, no play, no soft fur. When she saw me, Lassie would approach with hesitant hope—head lowered, tail uncertain. And I could not bear it. I did not know how to stay with the ache of it, the confusion of it, the raw injustice of it. I was angry at my mother for her neurotic cruelty but did nothing to protect my dog.

Instead I did what children so often do when they do not know how to handle pain: I looked away.

More accurately, I mentally erased the fact that I had a dog at all. I visited the bare minimum. I left quickly. I avoided feeling what I felt when I saw her. And in that evasion, I abandoned the very creature who had once been my companion.

She lasted only a year or two in that exile. When she died, I remember no ceremony. No ritual. My father dug a hole in that same miserable yard, and that was the end of it. I did not go. No words were spoken. No gratitude. No goodbye.

Even now, many decades later, I shiver with shame as I write these sentences. Her memory has always carried that sting.

But age has a way of revealing the deeper patterns beneath our earliest choices. My inability to face the pain of Lassie’s suffering, grew roots. It became the template for not talking to friends about what was really going on. For running for the hills when relationships with women I loved became emotionally complicated. For pouring myself into work rather than pausing to ask what I actually needed or wanted. For allowing even my children to fade into the background when life became too full, too fast, too demanding.

Looking away instead of leaning in.

Avoidance instead of presence.

Silence instead of connection.

It’s little wonder I have spent my entire professional life studying and teaching psychological flexibility – learning how to turn toward what hurts in order to move toward what matters. Those painful lessons began with a collie named Lassie, a friend I failed.

Today, as I write this, I close my eyes and shed a tear for her. I also smile—because she gave me joy and laughter and companionship, and those are real gifts. Even now I can feel her warm body pressed against mine on that living-room floor as we watched June Lockhart and the TV Lassie saving the day once again.

And in her honor, I again make a small vow: to be loving even when the prickles of emotional decomposed granite dig into my feet. To look toward what hurts rather than away. To stay present, even when presence costs something.

I’m not great at it. Perhaps I never will be. But I’m better than I used to be and that is worth something. That is my vow in action.

It is a vow born from regret, but also from gratitude for lesson learned. Lassie deserved better. The people in my life deserve better. And, truth be told, so do I.